One term that sometimes gets mentioned here by me and others via the comments section is “significance”. It is a statistical term that most readers are likely familiar with but many perhaps do not fully understand. Rather than try and explain it myself, below I have pasted an excerpt from the late Arthur Merrill’s August 1986 newsletter. It was passed along to me from a colleague a while back. I found it to be clear, concise, and a much better explanation than I could possibly write:

If, in the past, the records show that the market behavior exhibited more rises than declines at a certain time, could it have been by chance? Yes. If a medication produced cures more often than average, could it have been luck? Yes.

If so, how meaningful is the record?

To be helpful, statisticians set up “confidence levels.” If the result could have occurred by chance once in twenty repetitions of the record, you can have 95% confidence that the result isn’t just luck. This level has been called “probably significant.”

If the result could be expected by chance once in a hundred repetitions, you can have 99% confidence; this level has been called “significant.”

If the expectation is once in a thousand repetitions, you can have 99.9% confidence that the result wasn’t a lucky record. This level has been called “highly significant.”

If your statistics are a simple two way (yes-no; rises vs declines; heads-tails; right-wrong), you can easily determine the confidence level with a simple statistical test. It may be simple but it has a formidable name: Chi Squared with Yates Correction, one degree of freedom!

Here is the formula:

Χ2 = (D – 0.5)2 / E1 + (D – 0.5)2 / E2

Where D = O1 – E1 (If this is negative, reverse the sign; D must always be positive)

O1 = number of one outcome in the test

E1 = expectation of this outcome

O2 = number of the other outcome

E2 = expectation of this outcome

Χ2 = Chi squared

If above 10.83, confidence level is 99.9%

If above 6.64, confidence level is 99%

If above 3.84, confidence level is 95%

An example may clear up any questions:

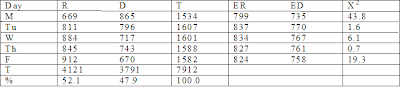

R = number of times the day was a rising day in the period 1952 – 1983

D = number of times it was a declining day

T = total days

% = percent

ER = Expected rising days

ED = Expected declining days

Overall, there were more rising days than declining days, so that the expectation isn’t even money. Rising days were 52.1% of the total, so the expectation for rising days in each day of the week is 52.1% of the total for each day. Similarly, ED = 47.9% of T.

For an example of the calculation of Χ2, using the data for Monday:

O1 = 669

E1 = 799

O2 = 865

E2 = 735

D = 669 – 799 = -130 (reverse the sign to make D positive)

Χ2 = (130 – 0.5)2 / 799 + (130 – 0.5)2 / 735

= 43.8, a highly significant figure; confidence level is above 99.9%

If expectation seems to be even money in your test, such as right/wrong), the formula is simplified:

Χ2 = (C – 1)2 / (O1 + O2)

Where: Χ2 = Chi squared

C = O1 – O2 (If this is negative, reverse the sign, since C must always be positive)

O1 = number of one outcome in the test

O2 = number of the other outcome.

[Chi squared is not always the correct statistical tool. When the number of observations is less than 30, Art used a test based upon the T-table statistic:]

The problem: In a situation with two solutions, with an expected 50/50 outcome (heads and tails, red and black in roulette, stock market rises and declines, etc.) are the results of a test significantly different from 50/50?

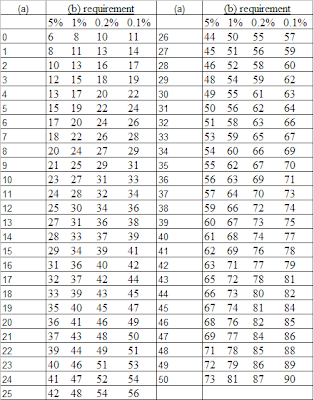

Call the frequency of one of the outcomes (a), the frequency of the other (b). Use (a) for the smaller of the two and (b) for the larger. Look for (a) in the left hand column of the table below. If (b) exceeds the corresponding number in the 5% column, the difference from 50/50 is “probably significant”; the odds of it happening by chance are one in twenty. If (b) exceeds the number in the 1% column, the difference can be considered “significant”; the odds are one in a hundred. If (b) exceeds the numbers in the 0.2% (one in five hundred) or 0.1% (one in a thousand), the difference is “highly significant.” Note that the actual number must be used for (a) and (b), not the percentages.

Example: In the last 88 years, on the trading day before the July Fourth holiday, the stock market went up 67 times and declined 21 times. Is this significant? On the day following the holiday, the market went up 52 times and declined 36 times. Significant?

For the day before the holiday, (a) = 21 and (b) = 67. Find 21 in the left hand column of the table; note that 67 far exceeds the benchmark numbers 37, 43, 48, and 50. This means that there is a significantly bullish bias in the market on the day before the July Fourth holiday.

For the day following the holiday, (a) = 36 and (b) = 52. Find 36 in the table. The minimum requirement for (b) is 56; 52 falls short, so that no significant bias is indicated.

Table for Significance of Deviation from a 50/50 Proportion: (a) + (b) = (n)

This is essentially the T-table statistic. It should be used instead of Chi Squared when the number of observations is less than 30.

Source: Some of the figures were developed from a 50% probability table by Russell Langley (in Practical Statistics Simply Explained, Dover 1971), for which he used binomial tables. Some of the figures were calculated using a formula for Chi Squared with the Yates correction.

In the next few days I’ll offer some opinion on the importance and use of significance testing.